A historical perspective of why Kashmiris observe Oct 27 as Black Day

Humayun Aziz Sandeela

Humayun Aziz Sandeela

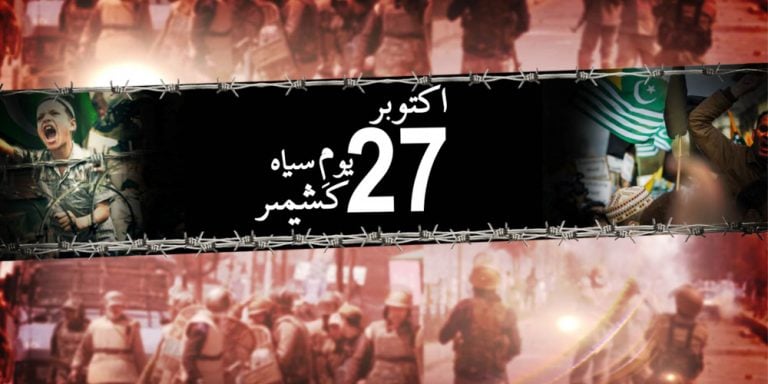

Every year on October 27, people in Indian illegally occupied Jammu and Kashmir and around the world mark Black Day to remember and protest the entry of Indian military forces into Jammu and Kashmir in 1947. This day symbolizes a painful chapter in the region’s history, as it commemorates the beginning of a long-standing territorial and political conflict that has deeply affected the lives, identity, and aspirations of Kashmir’s people.

The historical roots of October 27, 1947, lie in the complex circumstances surrounding the Partition of British India. At the time, princely states within British India were given the choice to join either India or Pakistan, considering geographical contiguity and the will of the people. Kashmir, a princely state with a Muslim-majority population but ruled by a Hindu Maharaja, Hari Singh, found itself in a precarious position. Maharaja Hari Singh initially sought to remain independent, hoping to avoid joining either dominion.

However, the situation escalated quickly. Reports suggest that communal tensions were rising, with accusations of the Maharaja’s forces committing atrocities against Muslim communities, particularly in Jammu. This unrest led to widespread displacement and further fuelled the drive for Kashmir’s accession to Pakistan, a sentiment shared by a significant portion of Kashmir’s population.

Amid this volatile environment, Maharaja Hari Singh signed the controversial Instrument of Accession with India on October 26, 1947. This decision provided India with legal grounds, albeit disputed, to deploy its military forces in Kashmir the following day, on October 27. Indian forces were airlifted into Srinagar, marking the start of what would become a prolonged conflict over the region.

Prominent historians, including Alastair Lamb, have extensively examined the events leading up to and following October 27, 1947. Lamb’s work, notably in Kashmir: A Disputed Legacy, raises doubts about the legitimacy of the Instrument of Accession and questions the official narrative surrounding Kashmir’s annexation. According to Lamb, the Instrument of Accession was potentially signed under duress and amid circumstances that were far from transparent. He argues that this document was, at best, a temporary arrangement meant to address the immediate crisis rather than a permanent solution to Kashmir’s political future.

Lamb’s research also highlights inconsistencies, suggesting that India’s military intervention was pre-planned and that Indian troops were already mobilizing for Kashmir even before the Instrument of Accession was signed. This raises critical questions about India’s commitment to a fair and just resolution of Kashmir issue, considering the pledges made by Indian leaders to allow Kashmiris the right to self-determination.

Following the accession, the conflict caught the attention of the international community. India brought the matter to the United Nations, and in 1948, the UN Security Council passed several resolutions urging both India and Pakistan to hold a plebiscite in Kashmir to allow its people to decide their future. Resolution 47 called for a ceasefire, demilitarisation, and the establishment of conditions for a free and impartial plebiscite. Although these resolutions were accepted in principle, they have never been implemented, leaving Kashmiris without the promised opportunity for self-determination.

For Kashmiris, October 27 is a painful reminder of unfulfilled promises, territorial disputes, and the loss of their right to self-determination.

The observance of the day allows Kashmiris to remember the moment when foreign forces entered their land, an act many consider an invasion rather than a protective intervention. For those who lost family members, homes, and security, October 27 is a day of solemn remembrance.

Over the years, the presence of the Indian military has intensified in Kashmir, leading to frequent encounters, curfews, and restrictions on civil liberties. The people of Kashmir use this day to protest the heavy military presence, which they argue perpetuates a climate of fear and undermines basic human rights.

By observing Black Day, Kashmiris bring attention to the fact that they are still awaiting the opportunity to determine their own political future. It is a reminder to the international community of the unfulfilled UN resolutions and the promises made by Indian leaders like Jawaharlal Nehru, who had assured that Kashmiris would be given a choice regarding their future.

Black Day has also become a unifying event for Kashmiris worldwide, transcending religious, cultural, and geographical differences. It reinforces a shared commitment to the cause of self-determination and serves as a rallying point for Kashmiris advocating for their rights on the global stage.

The observance of Black Day is not limited to Kashmir; solidarity events are held across the world by Kashmiris and their supporters. In cities like London, New York, and Islamabad, peaceful protests, seminars, and advocacy campaigns are organised to raise awareness about the historical and ongoing injustices in Kashmir. These events seek to inform the global community of the urgent need to address the conflict through peaceful means that respect the will of the Kashmiri people.

For the people of Kashmir, October 27 is not just a date on the calendar; it is a sombre reminder of a disrupted history and an uncertain future. Observing Black Day is both a reflection on past grievances and a renewed call for justice. As Kashmiris mark this day each year, they continue to strive for the realisation of their right to self-determination, a right that has been deferred but not forgotten. Through their observance, they keep alive the hope that the international community will one day recognise and support their struggle for a just and lasting peace.