On January 15 &16, 2025, the global spotlight will focus on Geneva as it hosts the World’s First Congress on Enforced Disappearances, a landmark event organized by the Convention Against Enforced Disappearances Initiative (CEDI), the UN Committee on Enforced Disappearances (CED), the Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances (WGEID) and the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR).

This historic event aims to galvanize international efforts to combat one of the most harrowing violations of human rights. However, the conspicuous absence of voices from Jammu and Kashmir, a region plagued by an estimated 8,000–10,000 enforced disappearances, raises profound questions about the barriers to representation faced by victims and human rights defenders alike.

Prominent human rights organizations in Kashmir, such as the Jammu and Kashmir Coalition of Civil Society (JKCCS) and the Association of Parents of Disappeared Persons (APDP), have been at the forefront of documenting and advocating against enforced disappearances. Led by Pervez Imroz, a distinguished lawyer and human rights activist and Parveena Ahangar, a tireless campaigner and founder of the APDP, these organizations have meticulously chronicled the region’s grim realities, from unmarked mass graves to systemic impunity for state actors. Despite their pivotal contributions to international human rights discourse, Imroz and Ahangar, like many other Kashmiri advocates, face severe restrictions on their mobility, with their passports confiscated and their voices silenced on global platforms.

This systematic suppression extends to institutions. The JKCCS, co-led by Khurram Parvez, has provided robust documentation of atrocities, including investigative reports on mass graves that have drawn international attention. Parvez’s incarceration since November 2021 under India’s sweeping counter-terrorism laws highlights the extent to which dissent is criminalized. Similarly, the APDP, under Ahangar’s leadership, has represented countless families of the disappeared, organizing monthly protests and ensuring the issue remains in public consciousness. Yet, these organizations, once vital conduits for information to the international community, are now effectively barred from participating in forums like the Geneva Congress.

The absence of these voices at such a landmark event reveals a troubling paradox. While the Congress seeks to fortify the plight of the disappeared and their families, systemic obstacles imposed by the Indian state prevent those most affected from sharing their narratives. This exclusion not only diminishes the authenticity of the discourse but also highlights the failure of international mechanisms to ensure access and representation for marginalized communities. Their work has earned global recognition, with Parvez receiving the Martin Ennals Award for Human Rights Defenders and Ahangar being nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize, yet their ability to advocate internationally is systematically curtailed. The confiscation of passports, arbitrary detentions and bureaucratic restrictions serve as tools to suppress accountability and isolate Kashmir from global scrutiny.

The history of conflict in Kashmir is deeply rooted in colonial legacies and shaped by post-independence geopolitical rivalries. Following the partition of British India in 1947, Kashmir became a contested territory between India and Pakistan. Between 1947 and 1987, the Kashmiri struggle for self-determination was largely nonviolent. In 1988, India escalated its efforts to suppress Kashmiris’ right to self-determination through militarization, deploying an estimated 6,67,000 military and paramilitary personnel in the region, approximately one soldier for every 17 civilians, signaling a significant intensification of the conflict. This militarization created fertile ground for human rights violations, including enforced disappearances, custodial killings and the establishment of unmarked mass graves.

Since the 1990s, enforced disappearances have been a defining feature of the conflict in J&K. Over 8,000 individuals, predominantly men between the ages of 18 and 35, have been forcibly disappeared. This practice involves state or state-sponsored actors detaining individuals without due process, often followed by torture, extrajudicial killings and disposal of bodies in unmarked graves. The International People’s Tribunal on Human Rights and Justice in Jammu Kashmir (IPTK) uncovered 2,700 graves containing over 2,943 bodies in just three districts, Bandipora, Baramulla and Kupwara. Many graves held multiple bodies, with 154 containing two bodies and 23 containing more than two.

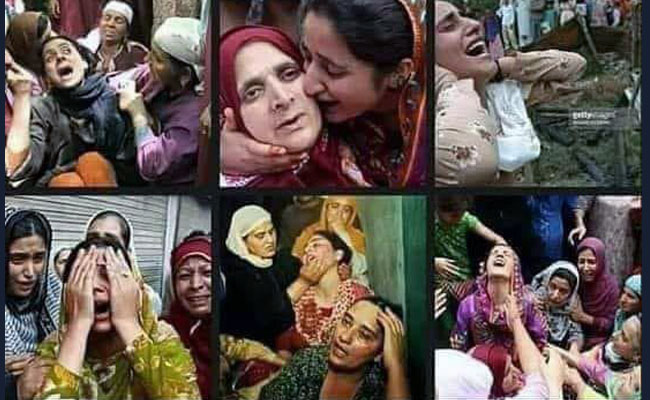

Testimonies from survivors and witnesses highlight the brutality underlying these disappearances. Corpses were often delivered under the cover of night, bearing signs of torture and burns. Local gravediggers, coerced into burying the bodies, described the dehumanizing conditions under which these acts were carried out. Despite claims by the Indian state that these bodies belong to “foreign militants,” local accounts and identification through clothing, distinguishing marks and exhumation efforts suggest that many of the deceased were Kashmiri civilians.

The Indian legal framework has facilitated a culture of impunity in J&K. Laws such as the Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA), 1958 and the Jammu and Kashmir Public Safety Act, 1978, grant sweeping powers to security forces, including the ability to detain individuals without trial. The AFSPA, in particular, provides immunity to military personnel from prosecution, effectively shielding perpetrators of enforced disappearances from accountability.

International law unequivocally condemns enforced disappearances. Article 7 of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court classifies enforced disappearances as a crime against humanity. The Geneva Conventions, to which India is a party, mandate humane treatment of all individuals, including those detained in conflict zones. Article 17 of the First Geneva Convention requires the proper burial of the deceased, while Article 121 of the Third Geneva Convention mandates official inquiries into deaths in custody. Despite these legal obligations, India has failed to adhere to international norms, as evidenced by the lack of transparent investigations or prosecutions related to mass graves and disappearances.

The consequences of enforced disappearances extend beyond the immediate victims. Families of the disappeared endure immense psychological, social and economic hardship. Women, in particular, bear the brunt of this tragedy, often assuming the dual roles of caregiver and breadwinner while facing societal stigma as “half-widows.”

An estimated 200,000 relatives of disappeared persons are actively seeking information about their missing loved ones, reflecting the profound human cost of this crisis. Enforced disappearances erode trust in state institutions, perpetuate cycles of violence and deepen grievances among affected populations. This creates a fertile ground for further radicalization and instability, undermining efforts to achieve peace and reconciliation in the region.

The global community has addressed mass graves and enforced disappearances in other conflict zones through robust investigations and justice mechanisms. The Argentine Forensic Anthropology Team (EAAF), for example, has played a pivotal role in uncovering the truth about disappearances during Argentina’s military dictatorship. Similarly, the International Commission on Missing Persons (ICMP) has investigated mass graves in Rwanda, Iraq and the Balkans, supporting legal proceedings and truth commissions. These precedents highlight the importance of forensic evidence, independent investigations and international cooperation in addressing enforced disappearances. In the case of J&K, similar measures could be adopted to ensure accountability and provide closure to victims’ families. However, India’s refusal to allow international observers and forensic experts into the region poses a significant barrier to justice.

This inaugural Congress, while a significant step forward, must not fall short of its purpose. The absence of Kashmiri voices serves as a stark reminder of the challenges inherent in pursuing justice for the disappeared. For the Congress to succeed, it must call for an independent commission to investigate mass graves and disappearances, urge the repeal of oppressive laws such as AFSPA and uphold the rights of those who speak for the disappeared. True justice demands such decisive and inclusive action.

–The author is head of the research and human rights department of the Islamabad-based think tank Kashmir Institute of International Relations (KIIR).